Last night I saw the Marty Supreme movie starring Timothée Chalamet. It features a host of interesting actors, including Gwyneth Paltrow, who played a fading actress, and Kevin O’Leary, the former Shark Tank asshole, who essentially plays a 1950s version of his present-day self in the role of Milton Rockwell, an ink pen mogul.

I’ve met plenty of rich assholes like O’Leary over the years, which is just one of the reasons the movie resonated with me. The real-life O’Leary shows up in my Linkedin feed, and I regularly comment on his ass-holey observations about American economics (he’s Canadian) and Trump, whom he resembles in being a hack TV star who leveraged his ass-holey personality on Shark Tank into acting roles. No spoiler alert here: O’Leary plays the ass-holiest asshole you can find in this movie. Still, in real life, I’ve met even more ass-holier guys than him during forty years in the marketing and media world.

That said, that’s still not the central reason I found this movie personally compelling. See, the main figure is a table-tennis-playing hustler named Marty Mauser. I grew up playing table tennis with my brothers. Our father built us a foldable table out of plywood. We set it up in the cramped basement of our Lancaster, Pennsylvania home, where we learned to contend with low ceilings, water pipes hindering certain shots, and the constant challenge of retrieving ping-pong balls from the dusty, spider-webbed recesses beneath the water heater and furnace.

We honed our game to speed and control, and at first, we used those pebbled rackets found everywhere in 1960s basements. We refused to purchase sandpaper rackets because they sucked, but whenever games popped up at social occasions or parties, we were prepared for the challenge and used whatever equipment was available.

Sometime in the late 60s, we discovered foam-rubber paddles made by the Butterfly company, and our games changed forever. Those new-style paddles offered far greater ball control. We learned “loop” shots, in which you struck the ball upward, creating spin that sent it off the table in an arc. We added spin shots, defensive “cut” shots, and highly controlled “push” shots from close to the table.

Our neighbors in Lancaster had a nice table, and we played them in table tennis all the time. Soon we entered school tournaments, where my older brothers won titles. They were both exceptional players, but my next-eldest brother, Gary, was the best among us four boys. His hand-eye coordination has always been exceptional as he also became a competitive fencer.

Once I entered high school, it was my turn to compete in school tournaments. I won the Kaneland High School (IL) table tennis tournament as a sophomore, and played in park district tourneys when we moved to St. Charles, IL.

There’s nothing quite like the nerves you get from playing competitive table tennis. There’s a psychology to every shot, and scoring points is a technical triumph. The lead character in the movie Marty Supreme shows this intensity well. Table tennis is a hustler’s game for some, but not all. Many player are all business, implacable. There are styles and versions of the game from all over the world. Eastern European. Asian. American. You never know who you’ll encounter in a table tennis tournament.

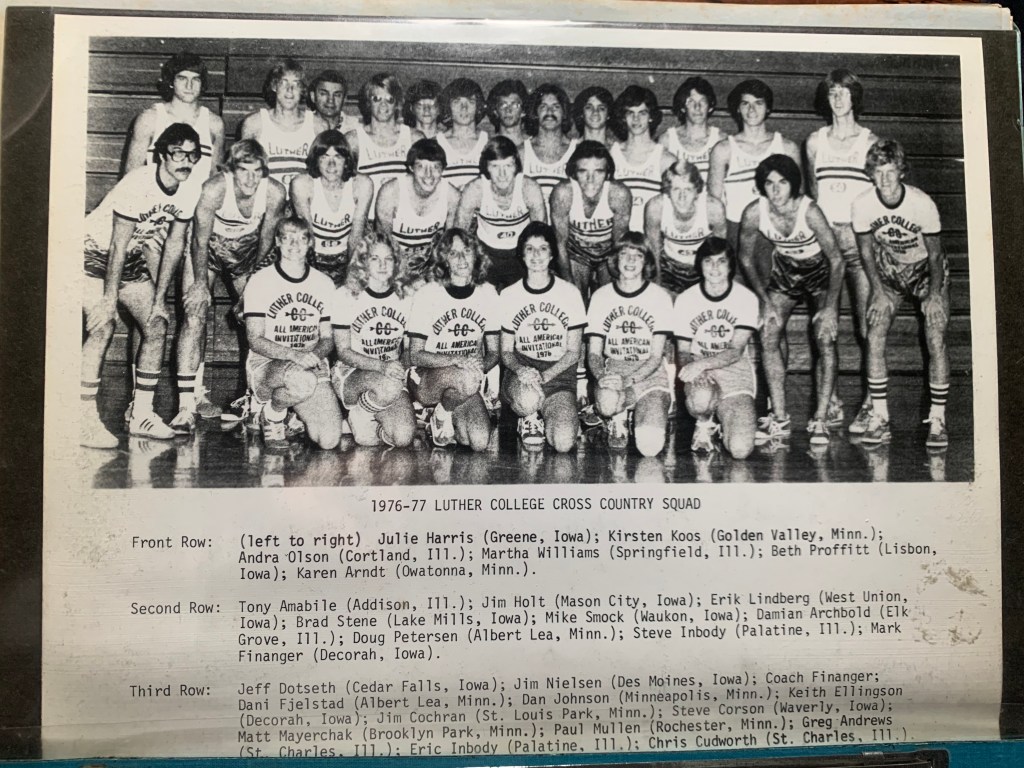

Upon entering college, I teamed up to play with a fellow cross country teammate Jim Nielsen. We played table tennis almost nightly in the freshman Ylvisaker dormitory at Luther College. Jim was a steady player who never quit. I don’t recall how often he beat me or not, but neither of us ever gave an inch. He told me we played doubles once in the college tournament, but I barely recall those matches. I think we lost to a Vietnamese duo.

I was focused on the individual tourney, but in the final match, I lost to Jeff Renken, the school’s All-Conference tennis champion. I don’t think I played in another college table tennis tournament after that. I was too mad at losing.

Cross country and track

Perhaps it was my running career from that point forward that consumed my focus for the other four years of college. Like Marty Mauser, I floundered a bit through realms of self-indulgence and damaged relationships. I had to hustle tough summer jobs, driving for U-Haul and working in a toxic paint factory to make money for college, and worked in the humbling role of dishwasher in the work-study program, and none of that really helped my running pursuits.

I was lonely too, and during my junior year, after surviving a semester studying the Philosophy of Existentialism and Jean Paul Sartre’s “No Exit” play, in which “hell is other people,” I decided that what I really needed was a woman to make me feel whole. I connected with a woman who was a virgin when I met her. She was a Christian keen on reading daily devotions, which I mocked in raw cynicism. We had sex often, and my track times dropped precipitously. Still, she was seemingly jealous of my running, or didn’t understand the dedication necessary to succeed, and she got me toxically drunk during a weekend trip to LaCrosse, Wisconsin. After that, I lost trust, but she was not happy that my interest waned. By year’s end, I was determined to break up and knew that summer break was an opportunity to do so. My father picked us up at college, drove us to the airport while she rubbed my arm from the backseat, and I said goodbye.

I confessed then to my father that I no longer, perhaps never really had feelings for her. “Well,” he offered, “At least she kept you warm for a while.”

The movie character Marty Mauser doesn’t treat women well either. He maligns them with his ego. “I have a purpose,” he tells the woman he’s impregnated. We were perhaps fortunate that didn’t happen with us. She went on The Pill. But she rightly expected that the man who took her virginity might marry her someday. I wasn’t honest about my intentions. I thought more like the guy in Bob Seger’s song Night Moves:

We weren’t in love oh no far from it

We weren’t searching for some pie in the sky summit

We were just young and restless and bored

Living by the sword

And we’d steal away every chance we could

To the backroom, the alley, the trusty woods

I used her she used me but neither one cared

We were getting our share

To this day, that’s not a relationship I’m proud of. That next year, I fell truly in love with a woman I dated for more than two years. We got separated by distance through work, and she quickly married another man. A year later, she asked me to meet up and talk things over. She said, “I made a mistake.”

These experiences are the “back and forth” of life. I could feel them seeping through me while watching Marty Supreme. The table tennis scenes felt authentic, and real. But so did Marty Mauser’s flawed obsession. After college, I dove even deeper into running, even taking a year off from work after being transferred out to Philadelphia in an asshole move by my bosses to consolidate the marketing department under a VP who was flirtatiously involved with our Assistant VP, it seemed, and the whole thing dissolved before my eyes.

Back to the Future

But I was given $7000 in severance pay, moved back to Chicago and trained like a maniac while living at 1764 N. Clark. Rather get a full-time job and save that money, I lived off those traveler’s cheques for months, but earned a sponsorship from a running store that paid my entry fees and provided shoes. I entered into a Marty Mauser hustler phase, and didn’t look back. I dated a woman in Chicago while keeping up my relationship with a woman in the suburbs. But ultimately, I got caught lying about that and ended the entire charade.

A year later, I married the woman whom I’d dated for four years. Just like Marty Mauser, I came to understand that there are values beyond personal interest and obsessions. My Chicago roommate had once come home from working his late-night job to warn me, “You know, self-indulgence doesn’t lead to self-fulfillment.”

I shared that observation with him years later, and he apologized. “I said that? I don’t know why. It wasn’t true.”

I’d also read a book by John Irving in which one of the lead characters insisted, when talking about wrestling success, “You’ve got to get obsessed and stay obsessed.” And that’s true. I come from a generation where an obsession with running was commonplace. I was far from alone in throwing myself entirely into the sport. I should have know that I had physical and mental limits when compared to far better athletes. But I improved during those three-to-four years of competitive running, setting all my PRs, and learned quite a bit about myself in the process.

I don’t know if that’s changed with this generation, or any generation. Marty Mauser played table tennis in the 1950s. There may be different versions of self-proscribed obsession in each generation, but one thing remains the same: we collide with fate and interpret it the best way we can in the moment. Hopefully, in the end, we make choices that make sense. Because after all, life is always a racket of one kind or another. That’s how I view Marty Supreme and Me.

End of game

One further note. Just a few years ago, my brother invited me to play table tennis with a club he’d joined. He bought me a new racket, a clean, new, paddle (see photo earlier in article) with two types of high-tech foam for competitive table tennis. I played a few times, but never won a match. The other players were too ‘practiced’ for me to catch up. It takes a ton of time to get better after you haven’t played in years. Plus, my hand-eye coordination is diminished with age. I found it too frustrating to lose every game, and didn’t have the competitive determination or the will to devote the time to regain an edge.

The game itself has changed. The table tennis ball is now slightly larger due to the speed of the equipment and skill of the players. Plus I have no patience for people whose table tennis game is strictly defensive, just returning every shot you make as their “weapon” to win. It feels cowardly to me, and I still have my principles when it comes to table tennis. I’ve never liked playing people who just crowd the table and bump it back at you. It’s annoying, but legal. It’s effective, and cheap.

So I quit playing. I’ll keep the racket and perhaps play for fun sometime. But lining up to get my ass kicked once a week just doesn’t align with my life’s goals. I doubt it would for Marty, either.