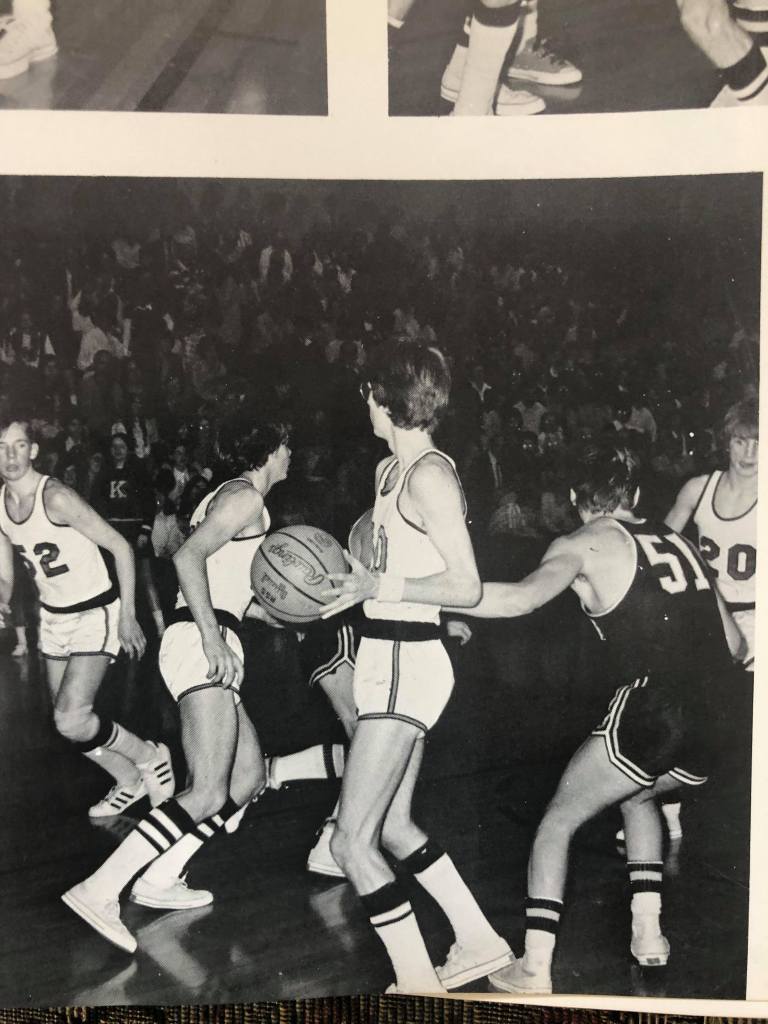

The summer before my junior year in college, my parents decided to move from a tiny split-level house in a suburban St. Charles neighborhood to a farmhouse six miles out of town. They were both raised on farms in Upstate New York. Perhaps they thought it would be nice to live out in the country again. Whatever the motivation, it wasn’t well thought out. My younger brother was still in high school on the other side of the Fox River. That meant it was an eight-mile trip one-way for him to get to school and basketball practices.

Coming home from college that summer was a bit disorienting. The farmhouse sat on a thousand acres covered in corn and hayfields. Those first few days I wandered the property trying to figure out what it meant to live so far out in the country.

There was plenty of room to run. The hills were plentiful too. But I’d forgotten one thing about running in the country. The dogs weren’t on leashes. On one of the first warm June mornings I was flying down the south side of a hill on Denker road when a large Doberman dog burst through the bushes and planted his nose firmly in my crotch while growling. I stood completely still, fearing that the next move might result in jaws and teeth embedded in my junk.

Instead, the owner came out of the bushes and called his dog back. I stood there a moment, not really daring to say anything to either the man or his dog. They disappeared through the bushes and I went on my way. Something about that day felt like an omen.

A week later while playing basketball with my brothers, we were dunking on a short rim when a loose ball rolled under the basket. I came down on the ball and twisted my ankle in a moment of fear and pain. That left me hobbled for several weeks. I wrapped the ankle in an Ace bandage and couldn’t run. That made me worry about fall fitness and cross country.

The other worry was finding a decent summer job. My mom heard that a friend’s son was working at a factory for Olympic Stain. He was a former basketball teammate so it seemed like a decent opportunity to share rides to work for the last half of June and the month of July.

And then I walked into a nightmare. The factory work was a Sisyphean mix of repetitive tasks and mind-numbing boredom. The first week was spent lifting Imperial gallons of liquid stain on and off a conveyor belt because the bailer element of the machine that installed wire handles on the cans kept breaking. That meant the cans coming down the belt would back up, and I’d have to stack them on the floor and back on the rack when the mechanic fixed the bailer.

Back and forth from our country house to the factory I went. The days mixed together in a bad way. Plus the guy with whom I shared rides was terrible at being on time. Work started at eight a.m. and I liked to leave our house by 7:20 to have time to get all the way down to Batavia, a good twelve miles away. But Johnny Be Late would show up at 7:45 because he was such a sleepyhead and couldn’t get out of bed on time. It drove me so nuts I even called his mother to let her know what a dweeb he was being. He’d mutter and apologize some days but honestly, he seemed not to care that much that he was always late. My hatred for him grew by the day. He’d even be late coming out of the house on the days that it was my turn to drive. As time when by there were many mornings that I didn’t talk to him at all.

It drove me insane to punch in late at that job. And without being able to run for those first couple weeks due to the sprained ankle, I had no way to wick off the stress of the whole circumstance.

The factory was also a chemical experiment in progress, with a blue haze of fumes from the turpentine used in the paint floating around the roof of the plant. The air we breathed was rife with the stuff, and a week into working there, a few of the regular plant workers conspired to play a prank on me, the dumb college kid.

“Here,” one of them instructed me. “Hold this hose down in the drum while we ‘shoot the pig’ to clean out the pipe,” he said, pointing to the long transport system leading from the turpentine tank to the mixing station. I stood there holding the hose into a drum already filled with turpentine when a rush sound came through the hose and a dense sponge traveling the speed of sound plunged into the turpentine drum. Instantly I was coated head-to-toe with a layer of toxic turpentine. It stung, and I felt it running down my hair and back. I looked up to see the line worker laughing has ass off. Then the foreman came running over and grabbed me by the arm. From there, I got my first introduction to the industrial shower. Naked and scared that I might die from poisoning, I stood there in hot water trying to wash the color and chemicals off my body.

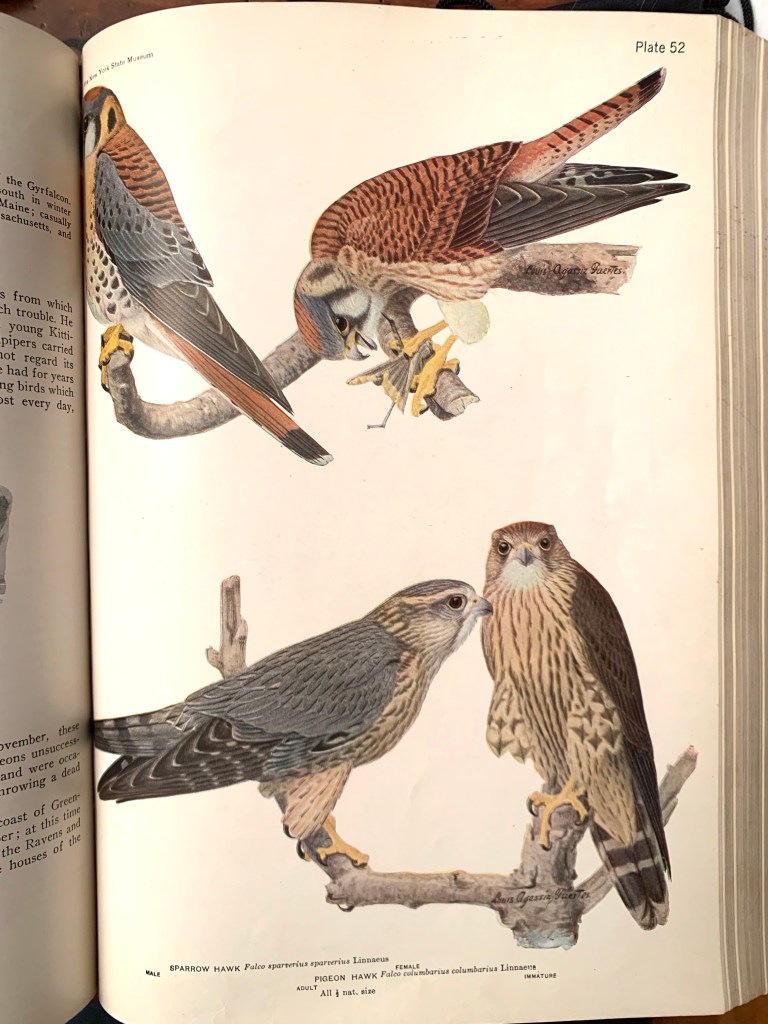

The culture inside the plant was built around constant teasing and verbal abuse. Mostly it was the divide between full-time workers and summer help that drove a form of spiteful commentary and behavior. It felt like a classic conflict between townies or locals. It was all a form of in-house bullying. I recall being mocked for not knowing what the term MoPar stood for. As the farthest thing from a motorhead the world had to offer at the time, I was disgusted to learn it was about nothing but car parts. It astounded me that someone could be so tribal and derisive about something so inconsequential to most of the world. While the people in my world were fascinated by Olympic aspirations, the people working in that factory were consumed with proving their worldview was superior in all its sordid details.

One of the guys I half-trusted was a former classmate from Kaneland High School named Phil. We took to making jokes with each other to pass the time and deal with the insanely toxic environment of that plant. Our humor took on a pattern of dark and disgusting jokes about different types of farts. Some of it was wordplay, like Brain Fart (not yet a colloquial term at the time) but I finally closed down the prolonged exchange by calling out “Blood Fart” across the sounds of the bailing machine and he replied, “Okay, you win.” I was way ahead of a future production of the same name.

Ywr ten years later, I randomly met Phil at a party of some sort. “Hey!” I told him. “Do you remember working together at Olympic Stain?”

“No. You didn’t work there,” he insisted.

“Yeah I did,” I reminded him. “We made up those fart jokes. That’s the only way that we could stay sane.” Then I looked closely at Phil. He was high as a kite. In fact, he was probably high the entire time we worked together at the paint factory. No wonder he didn’t recall a thing.

And yet, I saw him a few years after that and he recalled it all. Go figure.

After a few weeks of working on the paint floor, I got moved out to the shipping department and was glad for the change in routine. I learned how to use the handlifts to move skids of paint around. We loaded up trucks every day. Then an announcement came through the plant that the President of the company was going to pay a visit the next day.

We were all keeping busy when the President came out of the front office and was strolling down the aisle toward the dock when a guy driving a forklift came whipping around the corner with the forks raised. One of the metal prongs struck a stack of fifty-gallon drums three stories up and two of the giant cans flipped off and fell to the floor. The lid burst open and black paint went streaming down the aisle and washed over the President’s feet. He pointed at the forklift drive and commanded: “Fire that man.”

I went home that evening shaken by the idea that stuff like that could happen. I went

Finally, my ankle was improving enough to go for some short runs after work each day. But I noticed a strange fatigue that summer that I’d never experienced before. Was it the long days? Or was it breathing the chemicals in the plant all day long.

During work breaks, we’d retreat to the upstairs cafeteria to grab a Coke or in some cases, smoke a cigarette. The 30′ X 20′ space was nothing big, and it felt even smaller when people crammed in there smoking ciggies. I worried that the Blue Haze at the top of the plant ceiling might ignite one day from the tip of a lit cigarette. So I moved from the industrial blight of an open floor plan of a chemically compromised atmosphere to the enclosed spaces of a secondhand smoke science experiment. The wizened faces of the women sucking on on Kools and Marlboros seemed unconcerned that they might blow the place sky high. In turn, I pretended it wasn’t a risk.

For reasons unknown to anyone but the foreman, I was shifted back onto to the plant floor another week. He seemed to manage his job like a gopher filling holes that he’d already dug himself. So I dutifully moved into a position where the paints were being mixed and suddenly and briefly was given instructions on how to clean the pipe systems between the two 35,000 gallon vats of turpentine and liquid latex.

I just looked up the information about when OSHA laws were created, and it says they were put into place in1971. Yet here it was, in 1977, and I was being “trained” to conduct a highly dangerous industrial activity with one ten-minute session of training and no one to supervise me. Add in the fact that I am an ADHD learner and it was inevitable that disaster was about to strike.

The instructions were difficult for anyone to follow. The procedure required one to clean out the pipes on one side of the system, shut them down, then clean out the pipes on the other side of the system, and shut them down too. Then one had to conduct a pressure test, and that’s where things got weird. I turned the valve handle and liquid latex came shooting out from somewhere in that pipe system at an enormous rate. The fountain shot into the air and covered me from head to toe. I stood there in shock and recall trying to wipe the liquified rubber out of my eyes from behind my glasses, which were already stained a rust color from “shooting the pig” into a barrel of turpentine a few weeks before.

This time the plant manager came running over and shut down the pressure. Two people grabbed me and it was off to the industrial shower again. I could hear the floor employees laughing and saw them pointing at me. I was angry and scared and emphatically determined to pay them back for mocking me.

I stood naked in the shower until all the liquid latex drained down to the floor. My hair was matted and thick with the stuff, so I stuck my head under the showerhead for a few more minutes. Then I donned a set of company work clothes and went back out onto the floor.

All afternoon I heard taunts about the “Human Condom” while I worked the bailer in silence. I could not believe that I’d been put in the position of having to conduct a potentially dangerous activity like that. One guy in particular kep shouting insults at me, and I finally flipped him a gesture of discontent an he was so busy looking back at me that he’d forgotten to turn the Clarke floor cleaner in time to avoid driving off the railroad dock. The front-heavy vehicle tipped out the dock and sent him flying out over the tracks like a catapult. I stood there in shock for a moment, then shook my head and went back to work.

“Serves you right,” I muttered.

The next day I arrived late at work again thanks to my lazy-ass driving partner, and upon walking in the door was accosted by the plant foremone.”Listen,” he said. “If you keep showing up late you’re fired.”

Then he instructed me to go clean up paint under the main tanks at the west side of the plant. I walked over and inspected the area, which was coated with a fine layer of paint flecks and dust. I went to the closet and found a hoe-like device with a half-circle metal blade. For the rest of the day I chopped into the paint and found that there were layers of crusted, caked paint six inches thick.

I worked methodically chipping out the paint in six-foot squares. I was so sick of being late to work that I told my driving mate to fuck off and took my mom’s car to work every day. I’d punch in, walk to the closet to fetch the hoe-blade, chip away at the paint layers for several hours and slip off to have lunch at noon. Then I’d go back to work chipping paint again.

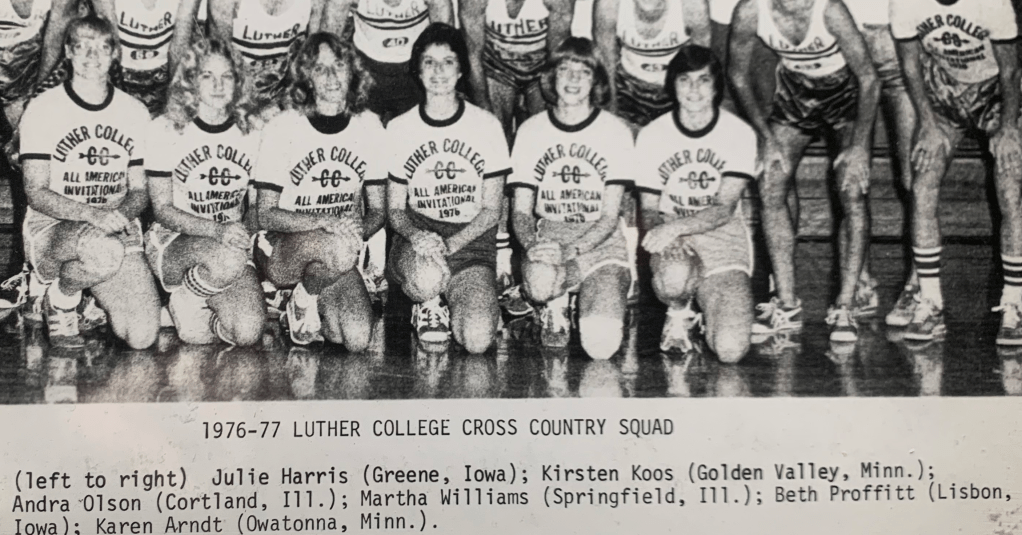

That went on for two weeks. I was deep into the rhythm of paint-chipping and relieved to be free of the insulting environment of the main plant floor. At night I’d go home to run a few miles before dinner, and worked my ankle and body back into summer shape. I’d lost four weeks of distance training thanks to the sprained ankle but decided that it was time to make the best of it. What I’d really missed was the stress relief that came from running. During that summer of working at Olympic Stain I’d begun to realize how important running was to my mental health.

Then one day I came into work and was chipping away at paint under the big vats when the foreman wandered back to find me doing what he’d told me to do. “What the fuck?” he asked, glancing around at the forty-by-forty-foot space I’d cleared under the paint vats. “Who told you to do this?”

“You did,” I replied.

“The fuck…” he responded. “Come on out here. We need you out on the bailer.”

I dropped the blade-hoe where I was standing and glanced back at the fine job I’d done clearing out that six inch layer of paint residue. If I’d done nothing else of value at that paint plant, I reasoned, at least I’d accomplished something visible and real.

The next day when I arrived at work, the foreman handed me a check and said, “We’re done for the summer. This is your last pay.” I snatched the check and walked out the front door of the plant. What a relief.

The next two weeks I spent trying to get in shape for cross country season that fall. But something creepy was going on with my body. I couldn’t get a full breath on some days. I realized that all those paint and turpentine fumes were messing with my lungs, my mind, and my self-perception.

I felt a heavy feeling in my head, like a sinking sensation at the back of my brain that both inexplicable and real. That was the first time in my life that I felt the effects of depression working on me. But it was time to go back to college. So I gathered all my stuff and rode with my older brother up to campus. He dropped me off with little ceremony and I hauled all my junk up the elevator to a dorm room in Dieseth Hall. On one hand I was happy to be back. On the other hand something felt vastly off about the coming year.

And then the fall training began.

Back home, my parents were having second thoughts about life on the farm. The commute to drive my brother to school and back was making them crazy. Plus the older couple from whom they rented the farm house was acting strange, accusing my parents of having too many people over to the house and weird things like that.

It all had an odd effect on my. Looking back on the entire circumstance, I recall that my closest friends recall the 1977-78 college period as “Cud’s Weird Year.”

And I can’t argue with that. Things definitely got weird in some ways.