One of the interesting aspects of endurance sports like swimming, cycling and running is that there is so much to share. Essentially, there are four ways to share.

- Share your experience. When you have knowledge to share, it can really help others.

- Share your experiences. When you train or compete, your experiences tell a story.

- Share your enthusiasm. Sharing love of the sport is a positive way to get feedback.

- Share your challenges. To overcome difficulties is part of the sport. Share it.

You’ll notice there is an inverse to the manner in which we all share. As a new participant in any of these activities, or all three when it comes to triathlon, the things we tend to share first are our challenges and enthusiasm. And understand, it is not uncommon for people to complain during this phase, or lament the results of their most recent workout or race. Still others will hit a plateau during training or races. These are forgiveable shares.

A group of training partners can be a valuable resource of friendship and shared experience.

That’s the hallmark of someone pushing themselves to do better. Progress is seldom a straight line proposition. So we verbalize those challenges as we get deeper into the respective sports.

The kid who lives behind me is a high school freshman. His middle school team won the state championship in cross country last year. He’s running six days a week now with the high school cross country team. Yet the first question I asked him was simple: “Are the other runners good guys?” And he answered, “Yes, most of them.”

Because that’s the most important thing in a training environment. How do the people around you respond to your challenges and your enthusiasm? Do they answer questions and share their experience? That’s the sign of a good environment.

Most of the time, this information-sharing occurs through people relating their experiences, not their experience. People usually don’t like to brag about what they know, or make themselves out to be know-it-alls. Instead, they share experiences or tell stories about their efforts in training or racing. These are meant to convey their experience.

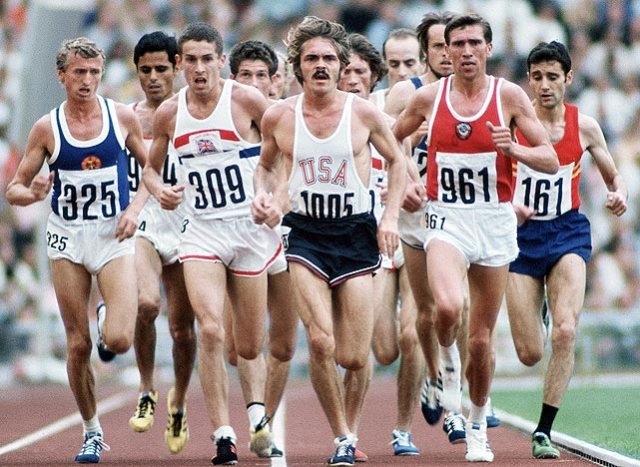

You may recall that Meb had some experience to share with Galen Rupp in the Olympic Trials marathon about how not to bump into other competitors.

Some of these shared stories can be funny. But often they relate a deeper truth. If someone throws up after a high school cross country race because they ate a donut just before the start, that’s a funny story. But it shares important facts about what not to eat when you’re about to compete.

So this sharing process plays an important role in all our development.

As a longtime distance runner, I’m learning that the most important thing I have to share is experience in how to train for races. People who pick up the sport of running or triathlon in their twenties, thirties, forties or beyond often do not have the baseline experience of running track or cross country in high school. As a result, they typically learn one way to train. Quite often that is doing their race pace in training, over and over again. Their methods may make them faster for a while, but ultimately they run into a wall of sorts. Progress ceases, and they wonder why.

The answer lies in aerobic thresholds and learning to train much faster than your desired race pace. It’s a simple rule: To get faster, you absolutely must run faster than race pace in training. Doing race pace over and over again may build endurance, but it has its limits in terms of building speed.

The trick, therefore, is to run paces that both physically and perceptually stretch your baseline race pace.

Of course, this is true in cycling as well. Yet most of us go out and barrel around at 18-20 mph on our own, thinking this will magically transform us into 22-24 mph cyclists. That isn’t going to happen. To ride much faster, you must do intervals at even faster speeds than your desired race pace. That would be 24-26 mph and better yet, even faster. If nothing else, one must get into a group that rides those faster paces and hang on for dear life. You may get dropped at first, but the goal is to stick a little longer every time.

That’s how the pros do it. And when they ride an easy day, they take it really easy. Their riding thus covers an entire range of speeds and aerobic needs. The really long slow rides build aerobic endurance while the speed training raises the heart rate.

Coaches often play an important role in picking us up when we’re down.

It is this knowledge and these methods that coaches are supposed to share with athletes. However, coaches can fall into a trap of prescribing the same types of workouts year after year because the formula works to produce certain types of results. A triathlon coach who gets people over the finish line in an Ironman is a valuable commodity. Yet that same coach might not be helpful to athletes seeking to refine a specific aspect of their triathlon performance.

That’s where event-specific coaching comes in. Or, you can opt to work with other athletes whose experience with ability and experience in those specific events. That type of shared experience is often free. Be prepared to ask when the opportunity presents itself, and most experienced athletes are quite willing to help. It’s an organic feature of endurance sports that your fellow athletes want to help other people in their sports.

This is tricky in a sport like swimming, where advice on proper swimming form can be conflicting on many levels. It is best to confine your form coaching to a set of specific, trusted resources. Ask other athletes who to trust, or hire a coach and stick to what they say. Nothing slows you down faster than trying too many things in your swim form. That’s asking for trouble, not help.

Be prepared to accept that there are some people who refuse to share their experience. But you typically don’t need them in your life. Sharing is something we’re supposed to learn and socialize in preschool. But the competitive nature of some people takes over. Even your close friends can become your worst enemies in training and competition. I advised my children when they reached late elementary school that it is often wise to realize your friends are prone to want to control you or leverage advantage in many facets of life. That’s not being paranoid. It’s a fact. Those same dynamics are played out in politics, religion, business and relationship. Human beings are competitive characters. And they aren’t always honest about their motives.

The heat of competition is no time to ask others to share advice.

Which sadly means that some advice is also best not taken without some consideration. People on the starting line of a race can be profound liars. I have been guilty of this manner of competitive lying. Yet I have also shared what I believe the truth to be in competitive experiences. While racing in a five-mile mid-summer race years ago, I knew that I was supremely fit and did not believe anyone in the field could beat me. A mile into that race, a competitor turned to me and asked, “What pace are you going to run today?”

I replied, “Faster than you,” and took off with a surge that left everyone in the dust. In that situation, I was not going to share an advantage of any sort. But why should I? There are some situations in life where winning or beating your rivals is the order of the day. There is nothing at all wrong with that. You can share stories and experiences after the racing’s done. Laugh or cry about the difficulties.

The one thing you are not obligated to share in 99% of most circumstances is your focus. yes, if someone is in need or you feel motivated to help another competitor out somehow, that is a great thing. That’s sharing yourself with someone in need. That is the greatest of all shares, if you think about it. And I’d say the first four types of sharing prepare you for that noble cause when it comes around.

In case you have not yet heard, the app

In case you have not yet heard, the app  So what evil parent dreamed this up?

So what evil parent dreamed this up? But there’s one place where Pokemon hunters cannot go. That would be your local high school track. Because over the last 15 years, running tracks have been turned into virtual prison facilities where only a small section of the public is allowed to go.

But there’s one place where Pokemon hunters cannot go. That would be your local high school track. Because over the last 15 years, running tracks have been turned into virtual prison facilities where only a small section of the public is allowed to go. Vandals rule

Vandals rule So there is a degree of irony in every chain link fence surrounding running tracks. Crawling over those fences is a risk unto itself.

So there is a degree of irony in every chain link fence surrounding running tracks. Crawling over those fences is a risk unto itself. It’s long been said you can’t protect people from their own stupidity. And it’s just a matter of time before some kid with his face stuck to his phone walks into a busy street while playing Pokemon Go and gets nailed by a garbage truck. The headlines will scream, “POKEMON GO PLAYER DIES IN TRAFFIC.”

It’s long been said you can’t protect people from their own stupidity. And it’s just a matter of time before some kid with his face stuck to his phone walks into a busy street while playing Pokemon Go and gets nailed by a garbage truck. The headlines will scream, “POKEMON GO PLAYER DIES IN TRAFFIC.” Days before the Lake Zurich Triathlon, I had not even registered for the race. There was a very good reason. The only races I was doing last week were to the bathroom to make it on time before calamity.

Days before the Lake Zurich Triathlon, I had not even registered for the race. There was a very good reason. The only races I was doing last week were to the bathroom to make it on time before calamity.

The run went just as well. I averaged 7:12 per mile without even knowing where we were going. Perhaps next time I’ll study up on that. Have a plan. But when your plan is just to get to the starting line without shitting your pants in some public place, the rest is not that important. The unstoppable Immodium Man plan was Plan A. Everything else was take it as it comes.

The run went just as well. I averaged 7:12 per mile without even knowing where we were going. Perhaps next time I’ll study up on that. Have a plan. But when your plan is just to get to the starting line without shitting your pants in some public place, the rest is not that important. The unstoppable Immodium Man plan was Plan A. Everything else was take it as it comes. Most of life is dealing with the consequences of your own actions. You make a choice and deal with the results. Sometimes they are good. Sometimes, not so good.

Most of life is dealing with the consequences of your own actions. You make a choice and deal with the results. Sometimes they are good. Sometimes, not so good.

But they sent me home with a plastic pan in which to shit, and I did that with rubber gloves covering my hands so that I could avoid contact with all those bad germs messing with my innards.

But they sent me home with a plastic pan in which to shit, and I did that with rubber gloves covering my hands so that I could avoid contact with all those bad germs messing with my innards. That also makes me wonder about people like Howard Stern, who pretty much does nothing on his show but talk about anal with his guests. And he’s one of the richest guys on the talent side of media. Which also makes you realize the real assholes all work on the ownership side. And that, my friends, cleanly explains the success of Donald Trump, who though he’s full of shit has gotten a complete pass from the media until recently. See, this shit all fits together in the end.

That also makes me wonder about people like Howard Stern, who pretty much does nothing on his show but talk about anal with his guests. And he’s one of the richest guys on the talent side of media. Which also makes you realize the real assholes all work on the ownership side. And that, my friends, cleanly explains the success of Donald Trump, who though he’s full of shit has gotten a complete pass from the media until recently. See, this shit all fits together in the end. Everyone in life has a history. And some of that history is baggage. Good baggage. Bad baggage. But baggage it is.

Everyone in life has a history. And some of that history is baggage. Good baggage. Bad baggage. But baggage it is.

Losing a first love like that is never easy. You don’t forget those feelings. Not when they helped form who you are. It’s true that high school girlfriends or boyfriends remain a part of your personality the rest of your life. You recall the fresh thrill of being liked or loved because it feels like nothing else you’ve ever experienced, or sometimes never experience again.

Losing a first love like that is never easy. You don’t forget those feelings. Not when they helped form who you are. It’s true that high school girlfriends or boyfriends remain a part of your personality the rest of your life. You recall the fresh thrill of being liked or loved because it feels like nothing else you’ve ever experienced, or sometimes never experience again. Now I’ve emerged on the other side of Bell Curve and am simply enjoying the entire ride when it comes to running, riding and swimming. But when it came time to clear out some running shoes and give them back for recycling, I noticed a pair of gray adidas with sweet red soles. I pulled them out of the pile and put them through the wash. They’re a little hinchy in terms of support because I wore them out running, but the adidas still feel good on my feet and bring back all those happy memories of early days in running.

Now I’ve emerged on the other side of Bell Curve and am simply enjoying the entire ride when it comes to running, riding and swimming. But when it came time to clear out some running shoes and give them back for recycling, I noticed a pair of gray adidas with sweet red soles. I pulled them out of the pile and put them through the wash. They’re a little hinchy in terms of support because I wore them out running, but the adidas still feel good on my feet and bring back all those happy memories of early days in running. At the end of a race, success or failure often comes down to whether you can will yourself to “gut it out.” That means going hard even when your stomach is in knots.

At the end of a race, success or failure often comes down to whether you can will yourself to “gut it out.” That means going hard even when your stomach is in knots. Recently I somehow developed cellulitis in my hand, perhaps from a small scratch. It spread across the back of my hand so I went to the Urgent Care Center and received a prescription for antibiotics. It took a couple weeks to knock out the hand infection, and I continued as instructed to complete the entire bottle of medication. Otherwise, infections can slip around the whack you give them and develop resistance. Then you have bigger problems.

Recently I somehow developed cellulitis in my hand, perhaps from a small scratch. It spread across the back of my hand so I went to the Urgent Care Center and received a prescription for antibiotics. It took a couple weeks to knock out the hand infection, and I continued as instructed to complete the entire bottle of medication. Otherwise, infections can slip around the whack you give them and develop resistance. Then you have bigger problems.

The notion of fitness is a key element of the theory of evolution. In nature, being fit for life means having the ability to survive. There are trillions of examples of this principle in operation every day. Evolution through time has delivered enormously complex organs, behaviors, and relationships that govern how species develop and survive.

The notion of fitness is a key element of the theory of evolution. In nature, being fit for life means having the ability to survive. There are trillions of examples of this principle in operation every day. Evolution through time has delivered enormously complex organs, behaviors, and relationships that govern how species develop and survive. For those who run, ride and swim, the ideal preparation for these events involves considerable training. This is because building endurance requires what we might call “chemical rehearsal.” With every movement we make, chemical reactions are taking place deep within our muscles and circulatory systems. We’re not simply a coat of armor marching around in the event we are challenged.

For those who run, ride and swim, the ideal preparation for these events involves considerable training. This is because building endurance requires what we might call “chemical rehearsal.” With every movement we make, chemical reactions are taking place deep within our muscles and circulatory systems. We’re not simply a coat of armor marching around in the event we are challenged. The trouble with these ostensibly Christian objections to the theory of evolution is that Jesus himself would never have abided in them. Jesus taught using parables founded in highly organic symbolism, and was thus a naturalist before there was such a thing. His symbolic use of images from nature to teach spiritual principles is called metonymy, the use of the characters of one object from nature to describe the attributes of another.

The trouble with these ostensibly Christian objections to the theory of evolution is that Jesus himself would never have abided in them. Jesus taught using parables founded in highly organic symbolism, and was thus a naturalist before there was such a thing. His symbolic use of images from nature to teach spiritual principles is called metonymy, the use of the characters of one object from nature to describe the attributes of another. And to that effect, every race of human being constitutes mere variations on a single species, homo sapiens, that has developed differences in appearance in response to specific climactic environments and other forces of nature. Yet for all this diversity, human beings from each of these variations can definitely breed.

And to that effect, every race of human being constitutes mere variations on a single species, homo sapiens, that has developed differences in appearance in response to specific climactic environments and other forces of nature. Yet for all this diversity, human beings from each of these variations can definitely breed. thers. Some possess better capacities to process oxygen or have hearts that pump blood more efficiently to the muscles. They have an evolutionary advantage, in other words, that predisposes them to success in human sports.

thers. Some possess better capacities to process oxygen or have hearts that pump blood more efficiently to the muscles. They have an evolutionary advantage, in other words, that predisposes them to success in human sports. The practical application of all this theory also suggests that your training must evolve over time. Changes in physical ability from ages 12-24 are profound. Athletes gain strength and endurance during these years as they reach maturity. Maximizing endurance from ages 24-34 is the goal, when most athletes reach their peak.

The practical application of all this theory also suggests that your training must evolve over time. Changes in physical ability from ages 12-24 are profound. Athletes gain strength and endurance during these years as they reach maturity. Maximizing endurance from ages 24-34 is the goal, when most athletes reach their peak. Beyond the age of 40, an athlete’s training absolutely must evolve in response to physiological changes occurring within the body. The human body loses some of its ability to recover from stress as we age. Our systems literally begin to wear out past the age of 40. This also mocks the idea that human beings once lived 600-800 years. Evolution defies any such claims on simple grounds that animal flesh simply burns out with time.

Beyond the age of 40, an athlete’s training absolutely must evolve in response to physiological changes occurring within the body. The human body loses some of its ability to recover from stress as we age. Our systems literally begin to wear out past the age of 40. This also mocks the idea that human beings once lived 600-800 years. Evolution defies any such claims on simple grounds that animal flesh simply burns out with time. Yes, there are some formulas for success, and good coaches abide by them. But great coaches also know how to adapt training to the athlete’s ability to respond. If something is not working, then an alternative must be found. This is especially true in response to the inevitable injuries that occur as a result of physical stress on the body from training. Plowing ahead when injury or illness catches up to an athlete is insane.

Yes, there are some formulas for success, and good coaches abide by them. But great coaches also know how to adapt training to the athlete’s ability to respond. If something is not working, then an alternative must be found. This is especially true in response to the inevitable injuries that occur as a result of physical stress on the body from training. Plowing ahead when injury or illness catches up to an athlete is insane. Of course, there are always those who want to game the process of evolution. That’s where practices such as using steroids, doping or blood infusion for endurance athletes enter the picture. When Lance Armstrong convinced his entire cycling team to engage in use of EPO, his doctor was simply applying drugs invented to help cancer patients maintain healthy blood oxygen levels to enhance athlete performance. The same held true with blood-doping, the extraction and reinfusion of blood into an athlete’s circulatory system. None of these methods would work without a complex understanding of the evolutionary processes behind athletic performance. The basic premise of the program was to help athletes exceed the body’s native capacity to produce blood and process oxygen. In other words, the goal was to become superhuman.

Of course, there are always those who want to game the process of evolution. That’s where practices such as using steroids, doping or blood infusion for endurance athletes enter the picture. When Lance Armstrong convinced his entire cycling team to engage in use of EPO, his doctor was simply applying drugs invented to help cancer patients maintain healthy blood oxygen levels to enhance athlete performance. The same held true with blood-doping, the extraction and reinfusion of blood into an athlete’s circulatory system. None of these methods would work without a complex understanding of the evolutionary processes behind athletic performance. The basic premise of the program was to help athletes exceed the body’s native capacity to produce blood and process oxygen. In other words, the goal was to become superhuman.

From the outside looking in, the sport of triathlon certainly looks insane. Magic Marker numbers scrawled on bare skin. Tight racing suits, radical sunglasses and a strange variety of hats and helmets. Bikes that look more like wine bottle openers than bicycles. Wetsuits that make everyone look like a beached seal or a giant black licorice stick. All while sweat or water is pouring down faces and other body parts. What’s this all about, really?

From the outside looking in, the sport of triathlon certainly looks insane. Magic Marker numbers scrawled on bare skin. Tight racing suits, radical sunglasses and a strange variety of hats and helmets. Bikes that look more like wine bottle openers than bicycles. Wetsuits that make everyone look like a beached seal or a giant black licorice stick. All while sweat or water is pouring down faces and other body parts. What’s this all about, really? That conversation

That conversation

All about the calves

All about the calves The pleasant little town of Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin is located just south of Kenosha along Lake Michigan. The triathlon conducted out of the RecPlex has gotten a deserved reputation as a great race. Reports from years past indicate the parking situation is much improved. Everything from registration to transition is within a nicely confined area.

The pleasant little town of Pleasant Prairie, Wisconsin is located just south of Kenosha along Lake Michigan. The triathlon conducted out of the RecPlex has gotten a deserved reputation as a great race. Reports from years past indicate the parking situation is much improved. Everything from registration to transition is within a nicely confined area.