Photo by Christopher Cudworth

In the early 1970s, I recall running along the roadside of Illinois Route 38 just north of Elburn where we lived. The east-west orientation of that highway with its raised road bed made it a perfect monarch-killing machine. Over just a milelong stretch between the intersection of Route 47 and 38 and the Elburn Forest Preserve a mile to the west, dozens of dead monarchs could be found lying in the gravel. They were all hit by speeding cars.

My brother and I collected them. We’d gather shoeboxes full of the insects. All that carnage was an indication of several likely scenarios.

1) there were more monarchs alive in those days or

2) our little town was right in the path of an important monarch migration route

Likely both scenarios were true. In all cases, the numbers of these insects was stunning. It is also amazing how far this species travels in stages from Mexico up to Canada and back.

Perhaps you’ve become familiar with the lifecycle of the insect called the monarch butterfly. Millions of monarchs that breed in the United States and Canada overwinter in the mountains of Mexico. That’s where conditions typically favor their survival during the winter months. But monarch lifecycles are changing.

As the linked article on phys.org describes, many monarchs have ceased journeying to Mexico and are hanging out in the southern United States where a certain species of non-native milkweed survives all winter. That has attracted monarch breeding, yet set the monarch population up for increased risk of disease.

The article states: “Long distance migration can reduce disease in animal populations when it weeds out infected individuals during the strenuous journey, or when the migrating animals get to take a break and move away from contaminated habitats where parasites accumulate,” she said. “Our non-migratory monarchs don’t have those benefits of migration, so we see that in many cases the majority of monarchs at winter breeding sites are infected.”

Changing climes

Some of this may be the product of climate change. As global temperatures continue to rise, the range of existence for a wide diversity of life forms expands and contracts. At climate extremes, such as high mountain terrain, alpine species are forced higher up the mountain face as increased temperatures alter the zone in which they can survive. But ultimately, they can run out of vertical and the adaptations of many species to their climate zones are formed over hundreds of thousands of years, not just a century.

When the “norms” no longer apply, human beings typically turn to technology to solve such problems. But other livings things aren’t always so fortunate. This much we also know: even technology can’t always compensate for the habits of greedy, stupid or stubborn people. We’re typically born with a fine brain, but survival all depends on how we use it.

So we depend on beautiful things at times to remind us not to be wasteful with creation.

Photo by Christopher Cudworth. Female.

Monarch ranchers

The facts are in across the land: monarch numbers are down these days for a number of potential reasons. The chief problem appears to be the agricultural eradication of the native milkweed plant species upon which monarch butterflies depend for breeding. They lay their eggs on the plants. Then small caterpillars emerge and munch out on milkweed leaves. It helps to “ranch” them to protect them from natural and unnatural predators.

Thus to help the monarch population, our family planted and grew milkweed in our garden. First, we’d search for eggs and pluck sections of the milkweed to bring inside and put into a water-filled jar. Soon the eggs would hatch into tiny caterpillars and those would start eating the milkweed leaves. They grow quickly into fat striped caterpillars and wind up reaching 1.5″ long. Then they’d climb to the top of the aquarium and affix themselves with tough silk to the screen top and curl into a tight ball. It all happens fast as the insects change from pudgy caterpillars into a bright green chrysalis with shiny gold flecks.

All rights reserved. No copies of this image may be made without permission.

My daughter Emily is an incredibly observant and patient photographer who documented all these stages in a series of images. She built a poster from these images. You can order one by contacting me at cudworthfix@gmail.com.

Payment is $21.60 by Paypal only. Size is 16″ X 20″ in high-res imagery. Shipping is $4.50. Total $26.10.

Watching the insects develop is a fascinating treat. But the real reward comes when the chrysalis form turns dark black and transparent after ten or so days inside the green chrysalis. That means the insects are ready to hatch into a full butterfly.

One year we ranched 50+ monarchs. There was a day when I released seven brand new butterflies outside in a period of several hours. The experience of watching these insects hang on their empty chrysalis shells while their wings pump into full form is incredibly inspiring. Being present for the “birth” of a living thing is both a humbling and affirming moment.

Holding a fresh new monarch as it clings to the end of your finger truly lifts your heart. Watching it hang a few minutes on a flower stalk in July with sunlight striking its brand new and colorful black and orange wings can be breathtaking. When the insects flap their wings and take off into a blue sky, it truly gives you a sense of wonder.

That’s a rare gift in this world where cynicism and the habit of taking the natural world for granted is so common.

The light in our eyes

Photo by Christopher Cudworth. Male monarch (black spots on lower wings)

So you might be asking, what does all this monarch talk have to do with running, riding and swimming? Well, I’ve known many endurance sports coaches who get the same sense of joy watching their athletes go through stages of development. That’s the literal take on how this all relates to running, riding and swimming.

“WE’RE ALL BUTTERFLIES!”

Okay, now that we got that one out of the way, let’s talk about a deeper perspective.

The richer meaning rests in all those days my brother and I spent walking the roadside during the height of monarch migration 40+ years ago. For it’s always hard to know, as young kids, what we’re supposed to recognize and know about the world. But when we grow into adults, it is important not to become jaded to what the natural world has to tell us. Because in that pattern of existence, we can begin to harm ourselves and others without ever knowing it.

We knew even back then that piles of monarchs along the road was not a good thing. But multiply that times how many east-west roads across the country? That meant millions of monarchs dead and wasted. So we collected them, and pondered that, and an environmental ethic began to form. Being nature-loving kids, we recognized that obvious lesson.

Butterflies aren’t free

But the deepest lesson of all is that monarchs are fortunately still with us. They have not gone extinct, as yet, and they are not “free” in the sense that their existence does not come without a cost. That would be protecting them. Advocating changes in agricultural policy. And even ranching them by hand.

Thus the arc from collecting those dead monarchs to raising and releasing them as grownups into the wild signifies a connection between ourselves and the earth’s systems. Even the Bible recognizes this important relationship. The parables told by Jesus were often founded on deeply organic symbols in a literary device we call metonymy, “the use of the character of one thing to represent the nature of another.”

We find this method of communication throughout the entirety of scripture. It is the organic foundation of the Word of God. Those who ignore that deeper symbolism do so at their own peril, for they miss the critical nature of what God is truly trying to tell us when we’re warned that life and creation are gifts from the universe. We’re not the center of it. Instead, it resides at the center of us. That is the heart of God.

Generations

Photo by Christopher Cudworth. Monarch on milkweed at dusk.

Passing something of value along to the next generation and the generation after is the greater gift of existence. Some of the monarchs that migrate north to Canada stop to breed, and the succeeding generation is the foundation of what travels south to Mexico. There is altruism even in nature, the sacrifice of one individual to pass along life to another.

This is a lesson important to human beings as well. Even if it’s the simple act of protecting what already exists, or at least not squandering creation on selfish grounds of greed or neglect, that is the basic responsibility of all human beings. Because despite the fact that some religious people see themselves as specially created and thus separate or superior to nature, they live in denial of what scripture actually tells us. Jesus saw beyond the legalism of such literal notions of relationship to God. His parables launched listeners into a greater spiritual connection, but they worked by using everyday examples from life and nature to do so.

So it’s not the end-all, be-all to simply say “God made this and I love it.” We have a duty to discern the greater patterns of nature and how they reflect creation as a whole. I personally embrace the notion of God but I also welcome the insights of those who do not. Wisdom comes in many forms, and butterflies can talk to us if we listen.

All a person has to do is hold a monarch butterfly on the end of their finger to know that life connects to life. Yet lacking that immediacy, we should at least appreciate that the insect fluttering over the fields has a long journey to make, and that our running, riding and swimming is a pale yet important imitation of the real thing.

That should be both a humbling and inspiring lesson to us all.

Iiiiiiiii rode my bike to work today. Not on purpose, mind you. The vehicle I normally take to work needed service. More than I thought. Took longer than I thought too. Soooo the option was hopping on the Specialized Rockhopper and pedaling up the Fox River trail to work.

Iiiiiiiii rode my bike to work today. Not on purpose, mind you. The vehicle I normally take to work needed service. More than I thought. Took longer than I thought too. Soooo the option was hopping on the Specialized Rockhopper and pedaling up the Fox River trail to work. I even found a bike trail along a road that normally takes me to work. But like all bike trails in this world that are tied to subdivision development, it came to an abrupt and immediate and all encompassing end. Just like that.

I even found a bike trail along a road that normally takes me to work. But like all bike trails in this world that are tied to subdivision development, it came to an abrupt and immediate and all encompassing end. Just like that. Which is why the Fox River Trail along the river is a quite nice way to commute to work by bike. No idiot drivers. Just me an the fat tire bike rolling along.

Which is why the Fox River Trail along the river is a quite nice way to commute to work by bike. No idiot drivers. Just me an the fat tire bike rolling along. Last night I led my daughter’s boyfriend Kyle on his first road bike venture. He’d grown up as a proficient and daring BMX racer, so the whole road bike thing wasn’t as threatening to him as it might be to others.

Last night I led my daughter’s boyfriend Kyle on his first road bike venture. He’d grown up as a proficient and daring BMX racer, so the whole road bike thing wasn’t as threatening to him as it might be to others. My point here is that Kyle will likely approach this road cycling thing in a different way than I have. What appealed to me about cycling was the liberty and freedom of rolling along at high speeds without having to run. Of course, I learned to change flat tires and how to adjust a thing or two on the bike so that I wouldn’t be stranded out in the cornfields. Beyond that, I remain a pathetic (apathetic?) novice at bike maintenance.

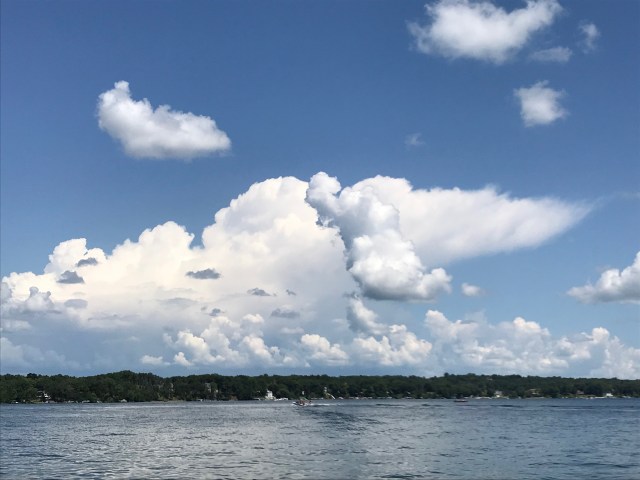

My point here is that Kyle will likely approach this road cycling thing in a different way than I have. What appealed to me about cycling was the liberty and freedom of rolling along at high speeds without having to run. Of course, I learned to change flat tires and how to adjust a thing or two on the bike so that I wouldn’t be stranded out in the cornfields. Beyond that, I remain a pathetic (apathetic?) novice at bike maintenance. The weather was fine and light. A storm had passed through an hour before so the clouds to the north towered 40,000 feet in the air. It served as an interesting backdrop to the rolling country road we traveled. On the downhills we soared past 20 mph and on the uphill Kyle experimented with the gearing. “It’s hard to get used to this,” he’d said earlier. “I’m so used to pressing down to make the pedals go. Being clipped in and being able to pull up is strange.”

The weather was fine and light. A storm had passed through an hour before so the clouds to the north towered 40,000 feet in the air. It served as an interesting backdrop to the rolling country road we traveled. On the downhills we soared past 20 mph and on the uphill Kyle experimented with the gearing. “It’s hard to get used to this,” he’d said earlier. “I’m so used to pressing down to make the pedals go. Being clipped in and being able to pull up is strange.” I’m not a slow bike rider. But I’m not a super fast bike rider either.

I’m not a slow bike rider. But I’m not a super fast bike rider either. My all-time fastest average was in a Masters 50+ race. When I got dropped after 35 minutes I looked down to find that I’d averaged 25.2. That’s pretty decent for a guy over fifty years old who only started riding seriously in his late 40s.

My all-time fastest average was in a Masters 50+ race. When I got dropped after 35 minutes I looked down to find that I’d averaged 25.2. That’s pretty decent for a guy over fifty years old who only started riding seriously in his late 40s. But the cycling is still a pursuit that I like to do as fast as I can. I’m not ready to grow the requisite full white beard that men of my age (too) often sprout. The signal they’re ready to slow down, retreat and fix their personal doctrine into permanent place.

But the cycling is still a pursuit that I like to do as fast as I can. I’m not ready to grow the requisite full white beard that men of my age (too) often sprout. The signal they’re ready to slow down, retreat and fix their personal doctrine into permanent place. For many people it is the light of autumn that seems romantic. As the sun courses lower in a September sky, shadows grow longer and trees take on a tinge of color. Come October, the light grows clear without the humidity of summer.

For many people it is the light of autumn that seems romantic. As the sun courses lower in a September sky, shadows grow longer and trees take on a tinge of color. Come October, the light grows clear without the humidity of summer. Entering my fourth year in college I fell in love with a girl under an August moon at an RA retreat in the hills of Wisconsin.

Entering my fourth year in college I fell in love with a girl under an August moon at an RA retreat in the hills of Wisconsin.

On the way to drop my wife off at the train, we were conversing about some domestic topic and I blurted out, “Well, I’ll have to put that on the Laundry List.”

On the way to drop my wife off at the train, we were conversing about some domestic topic and I blurted out, “Well, I’ll have to put that on the Laundry List.” Standing on the starting line of a five-mile race a few years back, I could feel the energy pouring through my body. Training had been going well. I’d done a track workout of 12 X 400 at 60-63 and was feeling sharp.

Standing on the starting line of a five-mile race a few years back, I could feel the energy pouring through my body. Training had been going well. I’d done a track workout of 12 X 400 at 60-63 and was feeling sharp. Unless you are so fit that your skinsuit looks like a coat of paint on your sculpted body, competing in triathlon typically requires a series of tradeoffs during each event. Swimming or cycling too hard in the first two stages can have a big cost when it comes time to run. More than one great cyclist in triathlon has busted a hard ride only to have jelly for legs in the run phase.

Unless you are so fit that your skinsuit looks like a coat of paint on your sculpted body, competing in triathlon typically requires a series of tradeoffs during each event. Swimming or cycling too hard in the first two stages can have a big cost when it comes time to run. More than one great cyclist in triathlon has busted a hard ride only to have jelly for legs in the run phase. A few years back when I started dating after the loss of my wife to cancer, I met up with a gal through eHarmony. She was a little older than me and seemed straightforward enough in our online chats. So we agreed to meet at a restaurant for drinks.

A few years back when I started dating after the loss of my wife to cancer, I met up with a gal through eHarmony. She was a little older than me and seemed straightforward enough in our online chats. So we agreed to meet at a restaurant for drinks. The Bible is a remarkable book both in what it reveals and also what it leaves to our collective spiritual imagination. For example, the creation story and the rescue of species from the worldwide floods lists a few “kinds” of animals that God created and preserved, but the record of nature’s salvation is far from complete. There only broad mention of the zillions of kinds of insects in this world, for example. Information about how Noah and the ark were able to provide food for creatures like tropical hummingbirds that specifically depend on flowering plants evolved by length of blossom to the length of the hummingbird’s beak is somehow missing.

The Bible is a remarkable book both in what it reveals and also what it leaves to our collective spiritual imagination. For example, the creation story and the rescue of species from the worldwide floods lists a few “kinds” of animals that God created and preserved, but the record of nature’s salvation is far from complete. There only broad mention of the zillions of kinds of insects in this world, for example. Information about how Noah and the ark were able to provide food for creatures like tropical hummingbirds that specifically depend on flowering plants evolved by length of blossom to the length of the hummingbird’s beak is somehow missing. The weather in Illinois was cool, rainy and windy this past Saturday. We rode west and north into the wind for 25 miles. At several points our speed dropped to 13 mph as we ground into the gray gale coming from the northwest.

The weather in Illinois was cool, rainy and windy this past Saturday. We rode west and north into the wind for 25 miles. At several points our speed dropped to 13 mph as we ground into the gray gale coming from the northwest.