We all make mistakes in life. Sometimes, it’s because we’re not present in the moment. At other times, we make choices that turn out to be wrong. And then, there are those times when we try to do all the “right things” and life kicks us in the butt.

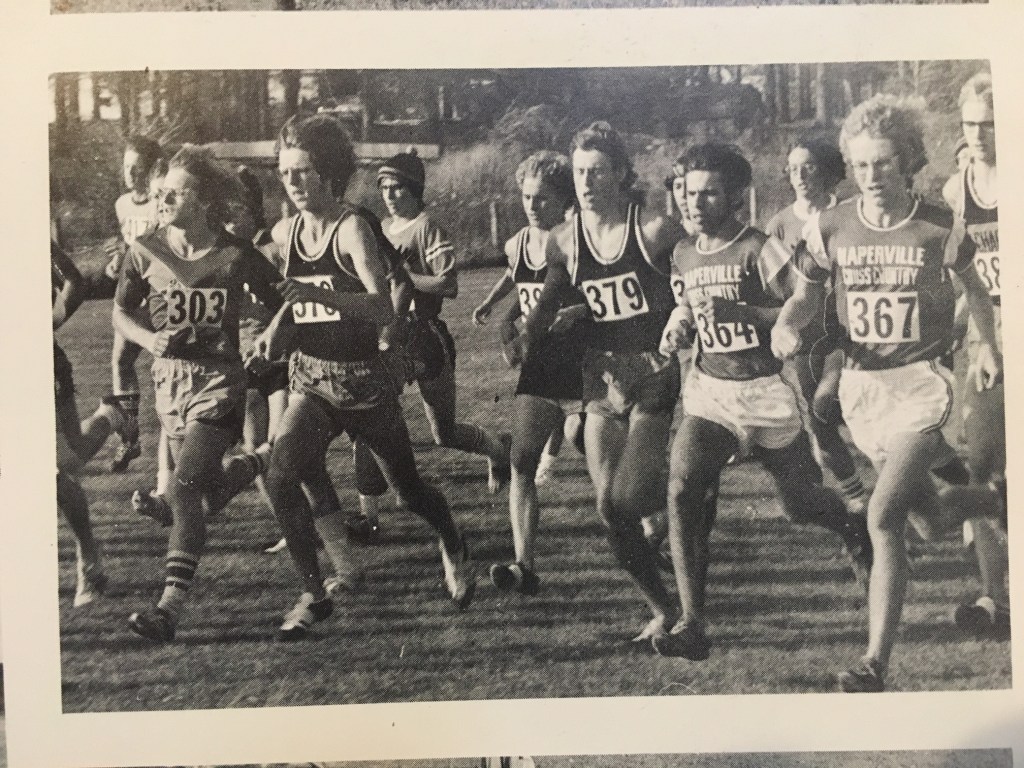

This photo shows the start of a cross-country race fifty years ago. I had just turned eighteen that summer. Our season started with a few weeks of training in the August heat. A few weeks into the season, after I’d won the first three races that fall, we traveled to the North Central College campus to run against Naperville Central, an annual powerhouse in the conference.

In 1973, as a junior at St. Charles, I led our team to a 28-29 victory over the Naperville Redskins (yes, that was their school mascot then) beating two of the top runners in the conference, Bob Warner and Rick Hodapp. Our victory snapped their 62 dual meet winning streak and set us up to have a 9-2 dual meet record ourselves that year.

As we set up to run against them again, a Naperville runner led us on the Course Tour. We ran along listening to instructions about loops and flags and other details. Perhaps I wasn’t paying full attention, or else the directions weren’t that clear that day, or my ADHD and competitive nature got in the way. After I’d taken off from the gun and built a 200-yard lead, I approached the college track with less than a half mile to go. Back then the North Central track was a cinder oval without fences. I swept down the hill approaching the north turn and swung right to repeat a loop around the track backstretch as we’d done on the first loop.

As I approached the middle of the track I felt triumphant that I was on the path to victory. But when I glanced across the track I saw that my rival Rick Hodapp had gone straight and realized that I’d run the course wrong. I’d either forgotten or neglected or never understood the final part of the cross-country course back then.

To this day, I think someone should have been at that critical turn directing runners to head straight to the finish rather than run a second loop around the track. A change in course directions the second time around was tricky to recall in the heat of competition. Recognizing my mistake that day, I sprinted like mad the rest of the backstretch and raced up the hill toward the finish chute Hodapp beat me by a mere four yards.

I was incensed and made it clear then that the race had turned out unfair. I earned no sympathy from the Naperville coaches who were happy to see Rick win the race.

Life isn’t fair, and that’s not all it isn’t

The lesson here is that life is often unfair. But in reality I’d caused that loss myself. That race in Naperville symbolizes life with an undiagnosed case of ADHD, a condition that would cost me in many other circumstances in life. From an early age, I struggled with certain kinds of learning, losing focus in classrooms where the subject or style of engagement bored me. When I was interested it wasn’t uncommon to earn As or Bs. But if I lost interest or missed even one bit of critical information at a given time, I’d struggle to catch up or grasp the lesson at all. The previous fall in 1973, I’d come close to flunking Algebra. As a senior, I barely made it through Economics and Government classes with Ds. My terminal boredom with the teaching methods and curriculum in those classes meant trouble with grades. Yet I received A’s in English where our teacher sat and read Studs Terkel stories to us all period.

These days I substitute teach and encounter students with many of the same learning problems I had. Over the years in the workplace, I’ve also met many people with ADHD. Some cope well, while others suffer the same embarrassing lapses that cost me in my career. One boss told me, “You do 9 out of 10 things great. It’s that one mess up that always costs you.”

The cost of caring

That fall of 1974 I’d also face a different kind of distraction. Following that Naperville race, my mother faced a life-threatening illness due to complications resulting from my younger brother’s breach birth decades before. I was four years old when my brother was born, and while my mother recovered that summer, I was shipped off to live with my aunt and uncle on their upstate New York farm. That year was formative in my love of nature and connection to the land, so it turned out to be a blessing.

But childbirth troubles have a way to coming back to haunt women. When my mom got sick in 1974, we were six or seven meets into the season. By then I’d won several races and pushed guys to the wire even if I lost. I was competing well overall. Then my dad took my younger brother and me to the hospital to visit our sick mother. We stood there anxiously staring at her in bed with the IVs and tubes attached and the machines beeping around her. We had no idea what to say, and no one said a thing about her prospects to us except our father, who told us, “She’ll be okay.”

Despite that assurance, I lost even more focus at school and in cross country. I lost the next three or four races. I’d take the lead but end up getting caught in the last mile. I just didn’t have the same mental strength I’d had earlier in the season. Seeing my mother near death upset me, but no one talked to me about mental health. I’ve always been a sensitive person, including anxiety and depression, which I also didn’t understand at that age. All I knew how to do was to keep running races and try to win. My girlfriend at the time was just a sophomore, the younger sister of a fellow teammate. I cherished her company but had to fill in the nature of my own misery in her presence. “I know you still love me even if I don’t win every race…” I offered.

I rallied eventually as my mother recovered at home after a period in the hospital. By season’s end, I’d won ten races and had enough fitness to finish fourth at a competitive district meet Rick Hodapp and Ken Englert, who I’d pushed to a record on his own course where we smashed into the finishing chute together, neither one giving an inch. He fell further forward than me and was awarded the victory that day. Just another bit of proof that life isn’t always fair.

After finishing fourth at Districts, I raced at Sectionals but my brain was close to mush from all the stress and distraction that season. I had a nervous sidestitch evident in the photos as I ran through the pain to finish in 15:51, a time well off my best that season, and one that placed me out of the qualifiers in one of the toughest sectionals in the state of Illinois.

That season symbolized how much of life has gone down for me. Overcoming distractions both real and realized, and learning to cope with fearful events is so much a part of life. All told I still won ten races out of 18 dual and triangular meets that season but ultimately, people judge you many times by the nature and style of your losses rather than what you’ve overcome to win.

Enjoy your blog, but got a weird message using your link. Did you lose control of your website domain?

Yes. I did. I’m trying to get it back.