What follows is an expanded version of an essay I recently entered in the Writer’s Digest Personal Essays writing contest. It aligns with this serialized “life story” I’m writing here on We Run and Ride. This is a slightly expanded version of the 2000-word entry.

Unfinished business

I knew that I was fit enough to win at the starting line of a five-mile running race on a cool spring morning. My plan was to run a 5:00 first mile, then pick up the pace and see who could go with me. At exactly the mile marker, another runner turned to me and asked, “How fast are you going today?”

“Faster than you,” I answered, and took off at a 4:50 mile pace, leaving everyone behind. I won the race in 24:49.

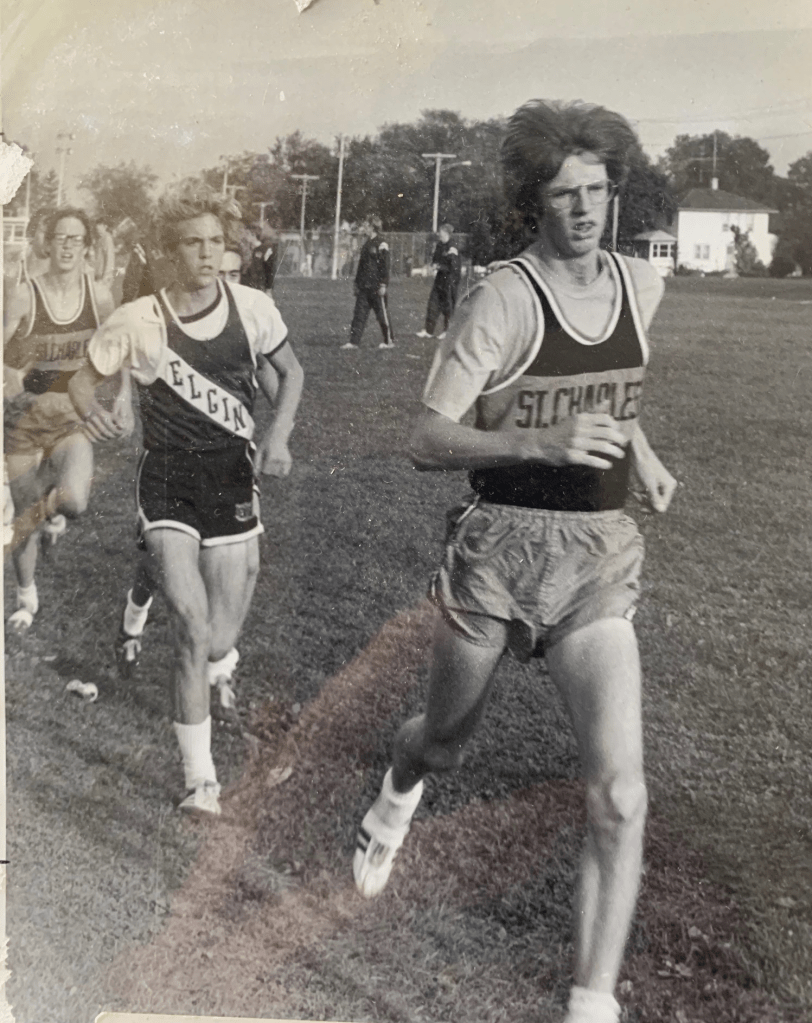

That’s how we rolled in the early days of the modern running scene. Winning races meant dispensing with posers and pretenders. It was harsh but true. During high school cross country, I’d won several races in a row, prompting a local newspaper journalist to brand me a “junior sensation.” My coach sought to set the record straight in that article. “Cudworth’s a good runner,” he observed. “But not a sensational one.” He was right about that. I ran against a far superior runner the next meet who confronted me at the starting line and snarled, “Junior Sensation my ass…” He beat me by thirty seconds that day.

Running is merciless in many respects, but the results aren’t always cut and dried. I once traded leads with another cross-country runner until we crashed into the finish chute and knocked it down. He fell a few feet ahead of me and was declared the race winner. I’d pushed him to a home course record by more than twenty seconds but never beat him during our many other encounters. Years later we talked about our rivalry on a social media runner’s group. He admitted, “You were a force to be reckoned with.” Such are the little victories over time.

My fascination with competitive running began with a twelve-minute time trial in seventh-grade gym class. Wearing a pair of Red Ball Jets sneakers and running on a cinder track, I covered 8 ¼ laps that day leaving most of my classmates behind. Our normally grumpy gym teacher acknowledged the quality of that effort. Yet when I got home that day and told my older brother about my time, he punched me in the shoulder calling me a liar. His doubt and insult burned inside me. I vowed never to let anyone question my running ability again. That was where my sense of unfinished business in the running world began.

The tests of will kept coming. In eighth grade, I expressed disinterest in playing badminton during gym class, so the P.E. teacher sentenced me to run laps around the lower and upper gymnasium for the entire hour. Rather than resist, I embraced that act of running rebellion. A friend pulled me aside after a full week of running laps and said, “You actually like this, don’t you?” I grinned and kept on running.

Heading into ninth grade, I was making plans to play football after winning the local Punt, Pass, and Kick contest. My father knew what was better for me in the long run. At age fourteen, I was a skinny kid at 5’10” and 128 pounds and might have been crushed playing football. On the morning of high school fall sports registration, my father walked me to the locker room door and warned, “You’re going out for cross country. If you come back out that door, I’ll break your neck.”

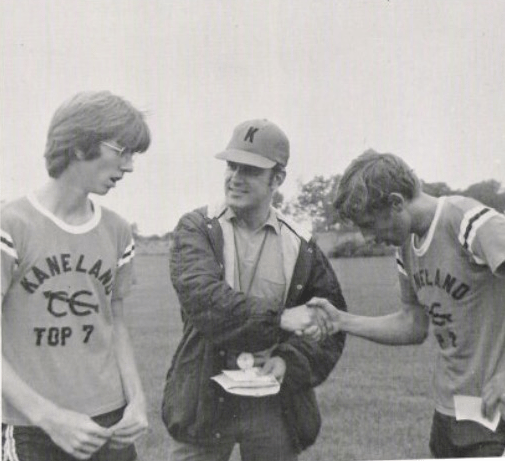

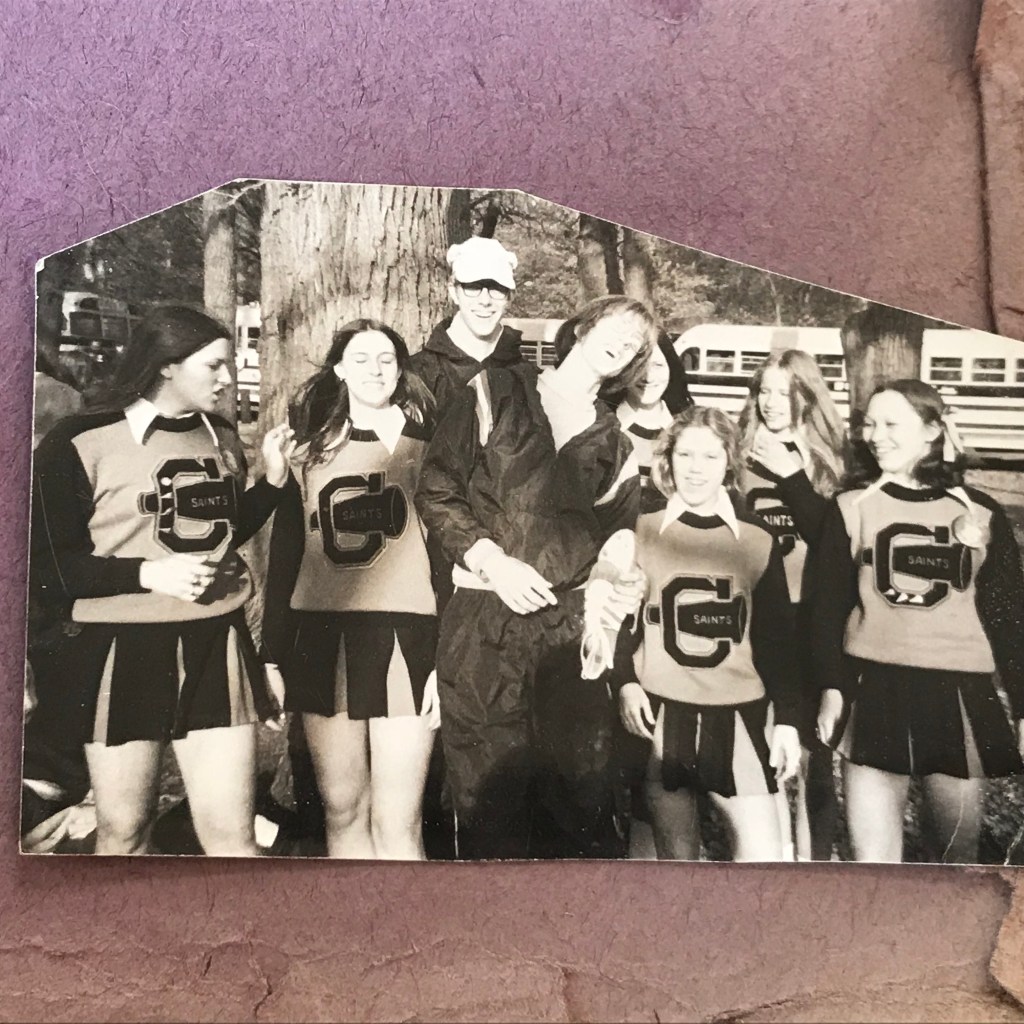

That was a life-changing decision in all the right ways. Forget all those pads and the smelly mess of the football locker room. All it took to make me happy was a pair of gum rubber flats, a set of running shorts, and a team tee shirt. I’d found a home in running and made the Varsity squad as a freshman that fall. The following year I was the top runner on a team that won its first-ever conference championship. Running became part of my identity.

Our family moved ten miles east to a different town the next year. At the new school, I again led the cross-country team while making friends that would last a lifetime. Early in the season, we raced against a team that had a winning streak of sixty consecutive dual meets. Before the meet, I sat on the school bleachers immersed in a literary masterpiece titled The Peregrine by J.A. Baker. He wrote about chasing wild falcons on the English coast, and my mind took flight from worry. I won the race while our team snapped the opponent’s dual meet win streak.

At that stage in life, I’d begun taking my writing more seriously and worked for the school newspaper while publishing prose and poems in our writing club’s journal. Story ideas often popped into my head during runs. That brand of hard exercise also helped me deal with native anxiety and an undiagnosed case of attention-deficit disorder. The flipside is neurodivergent hyperfocus, the ability to concentrate on topics or tasks of interest for long periods of time. Many of the greatest accomplishments in human history are produced by individuals with this superpower. Hence the cliché of the “absent-minded professor.” The distracted genius. There’s honor in that.

Some of my earliest educational experiences stemmed from the seeming inability to pay attention or remain on task. One year we crafted construction paper ships to track our progress in the SRA Reading Program. The ships raced around the room with each book we read. I lost interest after a couple dull stories and my ship lagged. My mother showed up for a teacher conference and appealed to my competitive nature to get me reading again. “Don’t you want your ship to keep up with the other ones?” she asked. I looked at the ships ahead of mine and replied, “I’ll wait ‘til they come around again and race them from there.” That response symbolizes the nature of coping with unfinished business when attention deficit takes over. We pick up where we can and move on.

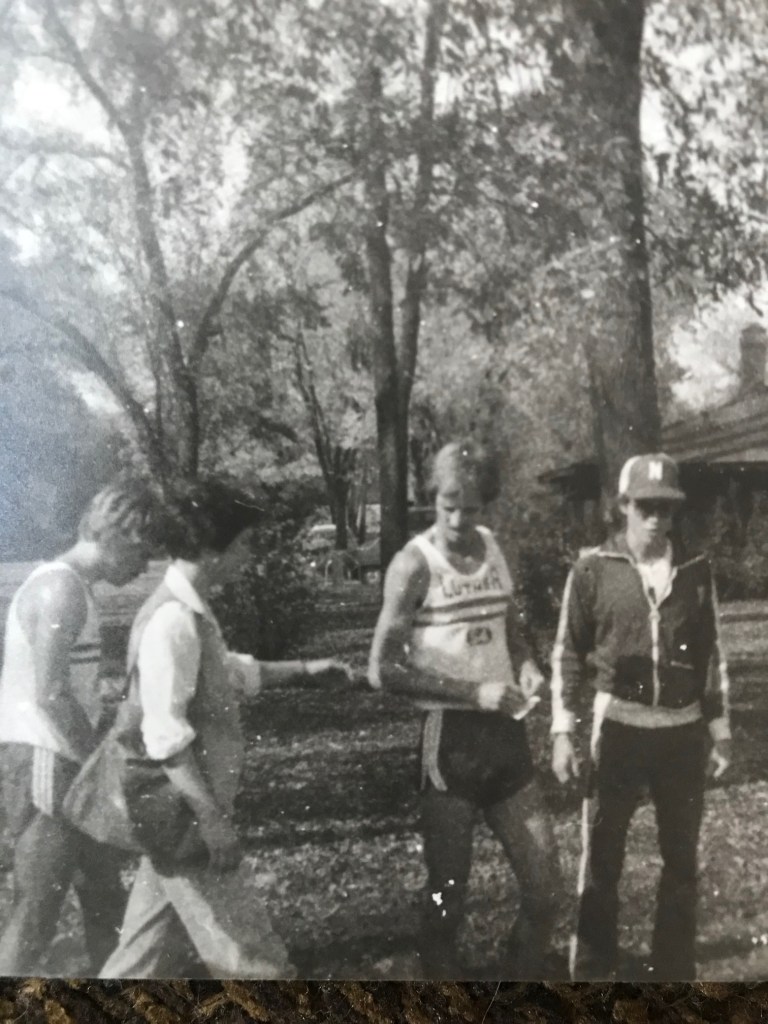

My busy brain was drawn in many directions as I pursued diverse interests in nature, sports, art, and writing through high school into college. I emerged with a Bachelor’s degree in Art and English, then drifted into an admissions counselor’s job as a means to stay close to a college girlfriend who still had a semester to complete before graduation.

I started admissions work that summer and that first month on the job required sitting in the office eight hours a day sending out recruitment cards to prospective students. My brain turned to mush. I responded by drawing cartoons to entertain myself and my colleagues. That restlessness did not amuse the Admissions Director. He pulled me aside and asked, “Is your head really in the game?” I answered that question emphatically, traveling 1500 miles a week during recruiting season to secure the 70-student quota from the city of Chicago and Illinois. During that year of travel, I stayed in the required low-budget motels and went for sullen runs to clear my head and keep my spirits up. When I complained to someone about the lack of time for running in my new job, their response was unsympathetic. “Welcome to the real world, kid.”

All that travel led to a breakup with the college girlfriend. Plus, her parents wanted her to marry a businessman, and I did not fit that mold in their eyes. Leaving the college world behind, I took a job in Chicago as a graphic designer for an investment firm. After a year the company transferred me to the Philadelphia office in a marketing department consolidation. By then, I’d fallen in love again and the thought of moving 750 miles east was another hard tug at the heart. “Oh boy, another long-distance romance,” I thought.

I rented an apartment twenty-five miles from downtown Philly in a small town called Paoli on the Conrail commuter line. There was a running shoe store a few blocks away that sponsored a racing team and I was invited to join. During the first training run, I took off running at 6:00 per mile pace like we did back in college. At two miles I was way ahead, so I turned around, ran back to greet them, and asked, “What’s wrong?”

“Nothing. What’s wrong with you?” one of them snarled. He told me, “Listen, we’re gonna run fifteen miles at 7:30-8:00 pace and do the last three miles faster. Can you deal with that?” I got the message and learned much more about proper distance training from a group rife with top-flight runners. On weekdays we gathered at the Villanova track for speed work. The rest of the week I filled with mid-tempo runs, yet still sometimes overtrained, coming down with colds and injuries. Once I achieved proper training balance my times dropped including my first sub-32:00 10K. Our team raced against other clubs almost every weekend. I’d found a new running reality.

The job in Philly ended when the marketing VP got fired and they cleaned house. I packed up and moved back to Chicago to share a Lincoln Park two-flat with a close friend and former cross-country teammate in high school and college. He was working day and night to complete his master’s degree. That meant I had tons of time to write, paint, and run. I joined a downtown track club and met some of Chicago’s best runners. The “Running Boom” was in full swing, and the Olympics were coming up in 1984. I made a journeyman’s vow to train full-time and complete the unfinished business of my running career.

That fall I won the Oak Park Frank Lloyd Wright 10K ahead of 3,000 runners. A week later I won the Run for the Money 10K race in 31:52 on a course deemed “at least 200 meters long” by one of the locals. After winning more races that fall, a running store offered sponsorship for the coming year. They paid all race entry fees, provided free racing shoes, a full team running uniform, and deep discounts on training shoes. I felt like a fully sponsored runner. Running was my life for the time.

With that focus in place, I set out to surpass all my running PRs. During a May All-Comers meet at North Central College, I lined up with 25 other runners for a 5000-meter race that was delayed until midnight due to the number of competitors in all the other events. The hour was late, but the conditions were perfect: No wind and temps in the low 60s. The pace went out fast and I passed through two miles in just under 9:20 and held on to run a 14:45 5K, a PR by twenty-five seconds.

I lowered my 10K road PR to 31:10 that summer and won a high-target race in a course record time that stood for the next twenty years. All told, I competed twenty-four times that year, won eight races, or placed high while setting PRs at every distance from the mile up to the 25K. I should have run a marathon that weekend, completing those 15.5 miles at a 2:25 marathon pace. By November, my body was exhausted. I dropped out of the last race entered but felt no shame. I’d hit my limit.

I raced more in 1985 with some great results, but a January engagement and June wedding turned my attention to future goals. The woman I married had stuck with me through the Philly move and my Bohemian adventures in Chicago. She’d seen me win races and there was nothing to prove to her or anyone else. The unfinished business of my competitive running career was complete.

A few years later, I openly lamented in my mother’s presence that I was perhaps self-indulgent in spending those two years running full-time rather than advancing my career somehow. She turned to me and said, “I don’t think so. You burned brightly.”

I tried to burn brightly over decades of life’s ups and downs that included years of caregiving during my late wife’s cancer and my father’s stroke recovery. Those years of mapping out running goals, building training plans, surviving intense workouts, and handling race stress bolstered my caregiving abilities, which are all about discipline, patience, and focus. Upon learning about my wife’s cancer diagnosis, my high school running coach called to offer words of encouragement, telling me: “Your whole life has been a preparation for this.” He was right. I was her primary caregiver through eight years of ovarian cancer survivorship. She passed away in 2013. We all miss her.

Over time I chose to date again and met a woman through the dating app FitnessSingles.com. She’s a triathlete and we share many other interests as well. I am grateful for her low-drama approach to our relationship. She doesn’t focus on my neurodivergence as a problem, instead offering gentle reminders on the to-do list, allowing me to catch up with unfinished business before it becomes a problem. That reduces the pressure in my head.

To this day, the benefits of running counteract my native anxiety and attention deficit disorder. I have been better able to handle professional life and avocations, but not without costs along the way. My ADD has at times resulted in job losses and difficulties in personal or professional relationships. The challenge of living with neurodivergence is real. Yet in some respects, finding my limits in running helped me put other pursuits in perspective. I still compete in triathlons, but my life’s primary focus is on writing and art these days.

A famous runner named Rick Wolhuter once said, “Pressure is self-inflicted.” He used that mind awareness to manage competitive anxiety and set world records. That insight is a bit of wisdom we can all use in coping with fear and uncertainty in life. The ability to manage distractions and find priorities is important to all of us. In my case, tackling the unfinished business of competitive running was symbolic of other challenges I’d face in life. What felt like self-indulgence in my early years turned out to be a helpful exercise on the path to caregiving, career, and self-fulfillment. I’m grateful for that.